Rage and Despair, in Response to Trump’s Executive Orders

By Marnie Thomson

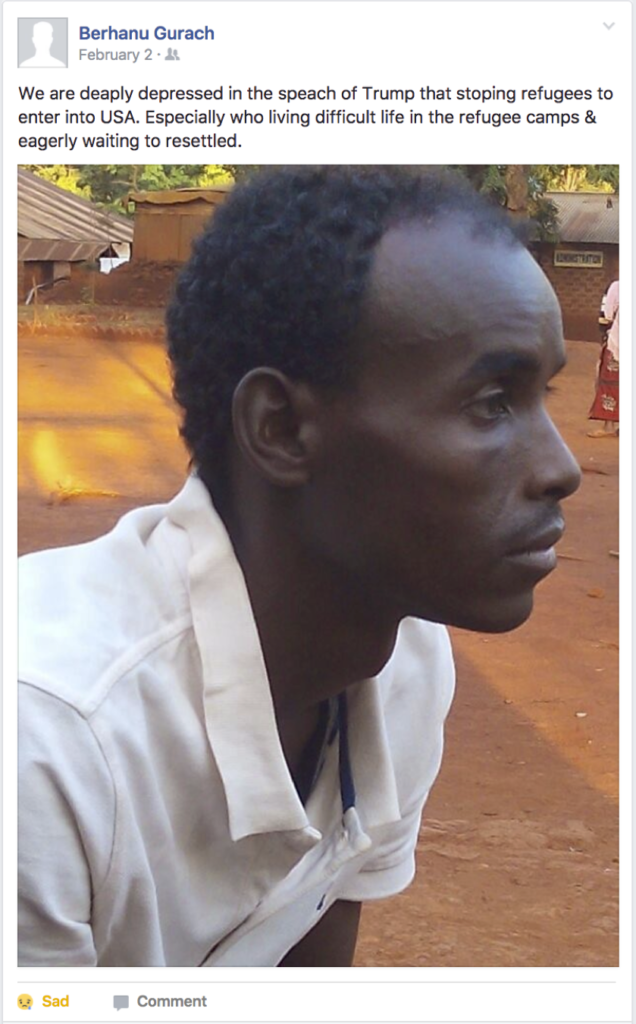

I share this Facebook post with the permission of Berhanu Gurach, an Ethiopian refugee who lives in Nyarugusu refugee camp in Tanzania. He posted this six days after Trump signed his first executive order banning citizens of specific Muslim countries and all refugees entry to the U.S.

Berhanu’s post represents the despair of refugees who endure in UN camps, clinging to the hopes of resettlement in the U.S. It expresses the dismay of those for whom promises of resettlement have now been reneged. His picture captures his raw emotion in the immediate wake of the first ban. Berhanu posted this before the first stay, and the ban had taken effect immediately, even in remote refugee camps like Nyarugusu.

During this time, refugees from Nyarugusu camp began asking me questions. “Why does Trump hate us?” “Why did Obama like us?” “What about the 30,000 that the U.S. promised to take from Tanzania?” “What is going to happen to us now?” Refugees who had already been resettled in the U.S. also had questions. “How does this order affect those of us who are already here?” “Will Trump issue an order about us?” The one question that refugees in the camp and those already in the US both asked me was: “What can we do?”

This is the ethical question I have been asking myself too. It stems from a place of dismay and distress. As Bianca Williams contends, emotion shapes not only how we embrace and understand social theory but also how we anthropologists position ourselves as allies and take action.

After the first Muslim/immigration ban, many anthropologists also took to social media.

Some joined the airport protests or started contributing to the ACLU and other organizations. The AAA called for the immediate reversal of the executive order. AES endorsed the AAA stance and contributed additional points in their own statement against the order. APLA/PoLAR issued a three-part response to the ban called Speaking Justice to Power. Six of us spoke out as anthropologists. In our classrooms, we spoke with our students about the implications of the ban.

Do anthropological ethics need to change in this new Trump era? In many ways, no. As Ruth Benedict said, anthropology’s purpose is to make the world safe for human differences. Yet as we work against racism, xenophobia, nationalism, white supremacy, and many other social injustices, we also need to take seriously anthropology’s complicity in creating today’s political landscape. In the special issue of American Ethnologist on the 2016 Brexit referendum and Trump election, Yarimar Bonilla and Jonathan Rosa urge anthropologists to unsettle our field, including recognizing the ways in which this political moment is not exceptional, but rather is consistent with both domestic and global political currents.

As part of unsettling anthropology, we need to ask: how should our ethical engagements change? How should they stay the same?

In a time where public anthropology may no longer suffice, Carole McGranahan suggests we take cues from the National Park Service and other governmental institutions and consider what going rogue would mean for anthropology. In her words, “Public anthropology is to be engaged. It is to communicate anthropological knowledge in a way that will be useful. Rogue anthropology is to be enraged. It is to communicate anthropological knowledge in a way that will disrupt, stop, resist, refuse.”

Rage, as Glen Couthard shows in Red Skins, White Masks, fuels the communal fire of resistance. By refusing and resisting Trump’s first immigration ban and seeking to disrupt and stop it, the anthropological responses mentioned above are the makings of a rogue or an enraged anthropology. What else might collective outrage mean for anthropology? Anthropologists should continue along the lines of producing swifter responses to more urgent matters. Anthropologists are well-positioned to respond quickly and incisively thanks to our longitudinal research, or what can at times seem like the field’s “unbearable slowness.” Our sustained commitments to specific communities also means that we can maintain the momentum of going rogue.

The federal court has overturned both of Trump’s executive orders. In some ways, however, the bans are still working. For example, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) has not been back to Tanzania since Trump signed the first order on January 27. This means that no new cases can be approved for resettlement in the U.S. Moreover, refugee resettlement quotas have historically been determined by executive order so there is no telling what that means for the future of refugee entry to the U.S.

Furthermore, where does this leave refugee hosting states and aid organizations? In Tanzania, for example, an entire aid apparatus has been built around resettlement in Nyarugusu camp during the past three years. The Tanzanian government, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), and its partnering organizations are now trying to figure out what to do with the infrastructure, funds, and staff they had designated for U.S. resettlement purposes.

Even overturned, the Muslim ban/immigration ban reverberates. Certainly, there are other communities of refugees, immigrants, and Muslims, as well as humanitarian organizations and state governments feeling its effects. This is not to mention the other executive orders and policy changes of the new administration. Anthropologists take their cues from the reactions of affected communities. Ethics, emotions, anthropology, and action are all entangled.

Just yesterday, another Nyarugusu resident messaged me to ask about the status of Trump’s order on refugees. He wanted all the details. I explained that a few days earlier I had corresponded with a UNHCR representative in Tanzania, who said that they were still waiting to hear if interviews for resettlement in the U.S. will resume. He was disillusioned to learn that there had been no new developments. As Renato Rosaldo has taught us, rage seethes with devastation and loss. This occurs even as emotional subjugation accompanies political subjugation, as Frantz Fanon has illustrated. Refugees’ disappointment, the UNHCR representative’s dismay, Berhanu’s despair: this is how we stay engaged and enraged. We stay tuned in—emotionally, ethically, anthropologically, and actively.

Filed under: activism, outreach and public anthropology, the state | Comments Off on Rage and Despair, in Response to Trump’s Executive Orders