Necessary Permissions…From Whom?

Scott Hutson

A critical point in the beginning of archaeological field projects and a necessary one according to the AAA statement on ethics (see statement 3) is getting permission from landowners. Yet sometimes this step is not as clear as it may seem. In an instance from my own fieldwork where a community rift threw doubt into the question of who could rightfully give permission, backing off from doing part of the research seemed like the solution. Before getting to the details, I provide some background.

In Mexico, where I work, the ownership of ruins is already tricky because of a distinction between the archaeological remains themselves (artifacts, crumbled buildings, etc.) and the land in which they are embedded. The buildings and artifacts are cultural patrimony of the nation as a whole, administered by the federal government, but the ground on which these remains sit can pertain to communal land-holding groups (ejidos) or private individuals and companies. The ancient palace of Zaachila, located in the center of the town of Zaachila in the state of Oaxaca, presents an example of conflicts that the distinction between federal ruin and local land can create. Two of the most decorated figures in Mexican archaeology, Alfonso Caso and Ignacio Bernal, each initiated research at Zaachila under the authority of the federal government but could not reach an agreement with a vocal group of Zaachila residents. In 1947, these residents ran Caso off the ruin, throwing stones in his wake. In 1953, Ignacio Bernal needed the protection of the federal army to re-start work at the site.

Getting local approval in addition to federal permission is therefore indispensable, but identifying the critical local stakeholders can be problematic. In cases where land is communally held by an ejido, the most common strategy is to begin by consulting with the ejido’s elected president and the officials he or she appoints. Yet the elected official often does not reflect the voice of all the ejido members, and conflicts within ejidos are common. For an outsider to such local politics, the best way to proceed may not be clear. The case I present from my own fieldwork in Yucatan (the Uci-Cansahcab Regional Integration Project) illustrates some of the contingencies that can come into play.

In the pseudonymous ejido of Chakche, most ejido members claim exclusive right of use to a small parcel of the ejido’s land. My goal as an archaeologist was to make a map of the ruins scattered across a rectangular block comprising more than a dozen of these parcels. My plans were presented and approved at an ejido meeting, but, as I found out the next week, one of the ejido members not present at the meeting—Jose—objected to the mapping. Soon afterward, Jose gave me a tour of the boundaries of his parcel so I would know where NOT to map. While walking with Jose I showed him some of the ruins we had mapped on adjacent parcels and talked to him about our goals, hoping he would change his mind about letting me on his land once he had a better sense of what we were up to. Jose finally suggested I could go on his land for a fee. As a counteroffer, I suggested I could hire him or a friend as part of the field crew. We could not reach an agreement. The next day, both the current ejido president as well as a former ejido president wanted to know whether Jose had given me permission. When I told them he did not, they suggested that I could in fact enter Jose’s land without his permission because the real title-holder to that parcel of ejido land was Jose’s recently deceased father. Since the title had not been formally transferred to Jose, the ejido president could act as the final authority.

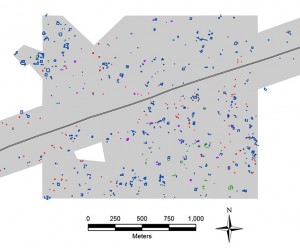

Amidst this lack of clarity over who was authorized to give permission, I chose to stay off the land claimed by Jose. Though this decision puzzled the past ejido president, it does not appear to have had a downside. Sure, it meant that my map would have a hole in the middle of it (see figure), but such a hole does not necessarily compromise the research. Richard Blanton and Stephen Kowalewski’s Valley of Oaxaca survey was a success even though it has a 40km2 hole in it, resulting from the ejido of Ocotlan’s refusal to let the archaeologists walk their land. To try to make up for Jose’s hole (as well as a divit in the north edge of the map boundary), my team surveyed some extra hectares in the northwest corner of the block, beyond the bounds of our original rectangle. This proved successful since what we found significantly expanded our understanding of the survey area as a whole.

Principle 3 of the AAA Statement on Ethics holds that anthropologists working with cultural resources, such as ruins, “have an obligation to ensure that they have secured appropriate permissions or permits.” The situation described above shows that it is not always clear who has the authority to grant such permission (see also Daehnke 2007). I end with two questions. When people in a community have conflicting ideas over whether cultural resources should be documented, what should anthropologists do? When we choose not to document the resources in question, are there ways to continue the investigation without “inappropriately changing the purpose, focus or intended outcomes” (see principle 4)?

Figure caption: Map of a portion of the area surveyed by UCRIP, in Yucatan, Mexico. The grey polygon represents the area that was surveyed. The colored items represent ancient features documented. The white “hole” at lower left is the area that we left un-surveyed.

Daehnke, J. D.

2007 A ‘strange multiplicity’ of voices: Heritage stewardship, contested sites and colonial legacies on the Columbia River Journal of Social Archaeology 8:250-275.

Filed under: archaeology, community heterogeneity, permissions and permits | Comments Off on Necessary Permissions…From Whom?